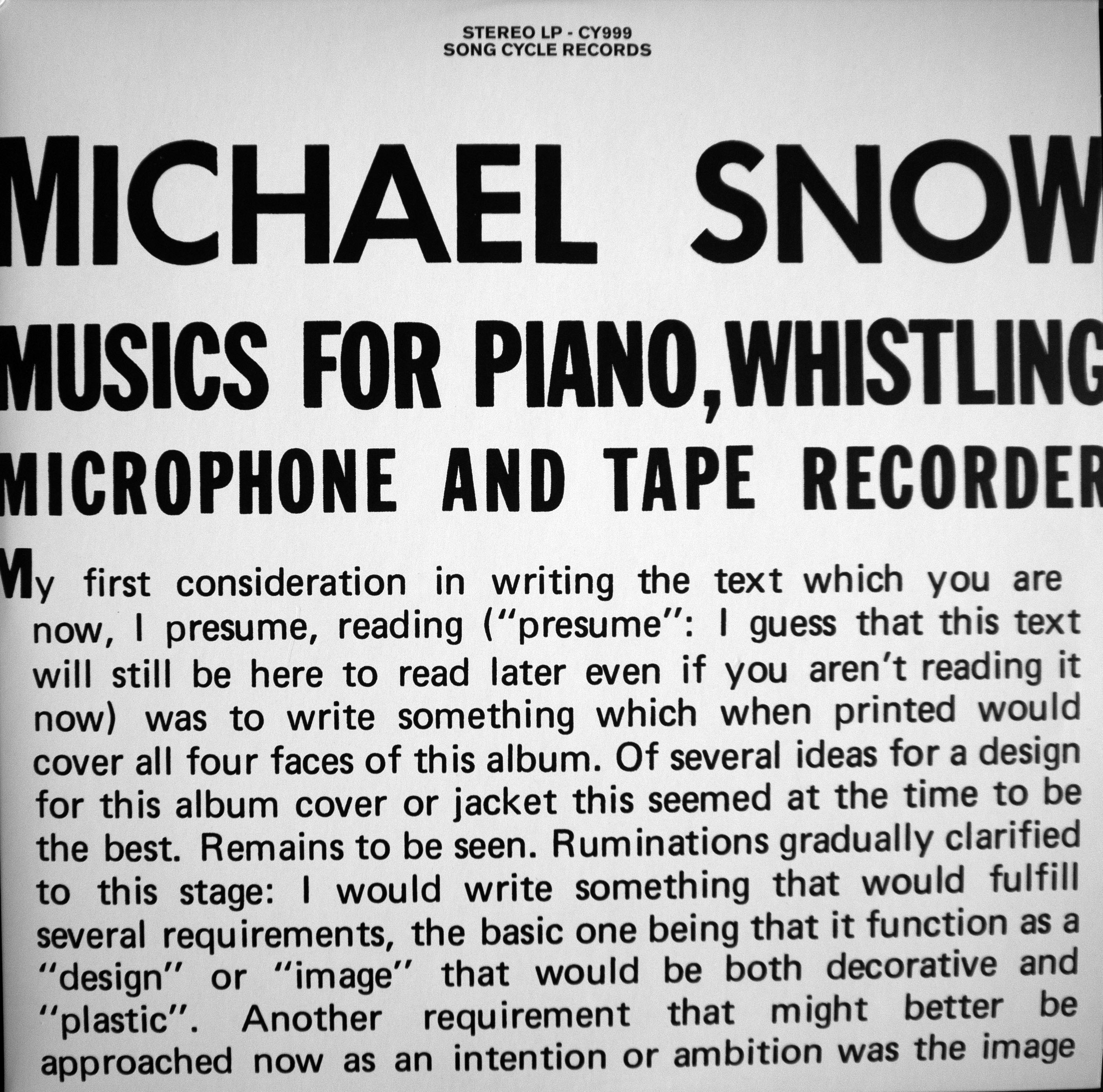

Contact I (July-August 2024) and Contact II, (January-February 2025), New Art Projects, London.

This pair of exhibitions was the most recent in a series of one-off screenings, events and gallery shows held in London since 2013, curated jointly by artists Andrew Vallance and Simon Payne. In this case Vallance was solely responsible for the exhibitions. Payne and Vallance first worked together on a lengthy series at Tate Britain entitled Assembly: A Survey of Artists’ Films and Videos. Their subsequent programmes have included expanded projection evenings and pairings of filmmakers who show and discuss each other’s work. They have primarily hosted events at Close-Up Cinema, Cafe Oto and a range of pop-up spaces and venues, some of which are now sadly defunct.

The two Contact exhibitions at New Art Projects mixed film and video with objects in which movement was implied or virtual, prompting a reflection on what ‘moving’ might mean in this context, given that ‘moving image’ is a problematically oxymoronic term, and apparent movement illusionary. All the work demands imaginative thinking on the part of the viewer to extend and complete it.

Jenny Baines’ Method over Matter (2024) is one of a series in which repetitive bodily actions involving strenuous balancing acts or the holding of difficult positions are presented as 16mm black and white film loops. Baines’ feet protrude from below into the frame in an urban setting. We’re invited to guess what’s happening below the screen: is she doing a handstand or simply propping up her legs while resting her back on the ground? This work encourages speculation on off-screen space and proposes a meta-critique: off-screen space in narrative films is necessarily a continuation of what’s in-frame to what’s outside it, whereas here we can’t be sure. Repeated actions are presented as loops, generating affinities, but important differences, between the actions and their form of presentation. This in turn poses the question of what precisely is the match or fit between a looping action and the film loop presenting it? The work is projected onto a screen stretched within a custom black metal frame, fabricated by Baines and based on her bodily proportions, thereby suggesting another affinity: the screen supports the frame as the artist’s body supports her legs. In creating a custom screen, Baines extends her thinking to the ways films can be presented without having recourse to the mostly homogenous formats used in gallery installations, such as floor to ceiling flat screens, for example. Productive failure, futility and exhaustion are key structuring principles in her work. Repeated, purposeless physical actions are filmed for the length of a full wind of the Bolex 16mm clockwork camera. When the camera runs out, after about 23 seconds, the shot ends abruptly. For each repeat, more or less of the action is completed, depending on various imponderables. For the viewer there is a palpably physical-empathic response that corresponds to the way Baines fails to complete an action: one invests a quasi-physical urge to her to succeed so that one feels her failure as one’s own. Baines’ work reinforces the importance of the non-utility of art, the creativity of futility. It is particularly pure and direct in this respect, contrasting strongly with so much contemporary art, which manifests the need to address political or other concerns outside of art’s proper means and forms.

Jenny Baines’ Method over Matter (2024)

Cathy Rogers works with implied or latent movement in her lightbox series, including Miscanthus (2024), composed of a photogram of a plant made on a rectangular arrangement of adjacent strips of 16mm negative. In seeing these composite images, we can try to imagine how they might look if joined together and projected. In his canonical film, Ten Drawings (1976), Steve Farrer used a similar technique, but painted and sprayed images onto the strips, which were then joined together to make a projectable abstract film. In Farrer’s film, a graphic flatness is preserved throughout the process and the film is a form of animation. Rogers’ work, by contrast has often involved a critical engagement with varying degrees of dimensionality to a greater or lesser extent, complicating the transformational relationship between the three dimensionality of objects in space and the two-dimensional flatness of contact prints and photograms. Rosemary, Again and Again (2013) was made by draping unsplit Standard 8 (16mm wide) film around a rosemary bush and exposing it to light. Parts of the film are in contact with the plant, but others not, resulting in varying degrees of sharpness (sharpness, as opposed to focus, which implies the use of a lens). When projected this results in a stream of more or less soft shapes that merge in the eye, but periodically a sharp edge cuts through and violently asserts the surface of the film, the contact between leaf and filmstrip. Although the work is linear in the sense that the filmstrip preserves a physical, linear relationship with its subject, the experience is spatiotemporal: time rearticulates the original a-temporal spatiality of the making situation (the entire filmstrip having been exposed at the same moment). In Miscanthus, by contrast, the original spatiality of the making situation is preserved in the image and temporality is absent, except in the mind of the observer, who can imaginatively speculate on what the work might look like as a projected film. Imaginative speculation is thus at the heart of Rogers’ work in a similar way to Baines’.

Cathy Rogers Miscanthus (2024)

Baines’ work links to that of Carali McCall and Sophie Clements (discussed below), both of whom also work with gruelling forms of performance. McCall’s Circle Drawing 1h 55 minutes, from an ongoing series (2012-24) involves a repetitive, live drawing process that continues until she is exhausted. The drawing is a residue of the action, and in looking at it we can try imaginatively to retrace that action. Doing so involves thinking through what retracing minutely involves: how do we disentangle the overlapping loops? Or do we disregard the way the work was made and consider it as a self-sufficient drawing? I would say not, and since the work announces its making process we need to think about the relationship between the process and is outcome.

McCall raises questions around intentionality: what are the consequences for work that’s made by a body at the point of exhaustion, where loss of control gradually increases and extra effort affects the way familiar, rehearsed or even simply impulsive moves are compromised? In 2005, the improvising guitarist Derek Bailey released an album, Carpel Tunnel, from whose syndrome he was suffering as a complication arising from Motor Neurone Disease. Over a period of 12 weeks, he recorded a series of pieces that evidence the gradual loss of agility in his right hand. In the first track he discusses the effect on his playing. He’s been advised to have an operation but he would prefer to find a way round the problem. Certain clusters of notes, he says, sound better played without the plectrum he can no longer hold. This generates a problem of intentionality. Anecdotes about Jackson Pollock’s handling of paint point to his highly developed level of control, but such claims can seem apologetic, as if needing to defend what could be seen as an abnegation of skill and responsibility. There’s an anxiety about the importance of agency in the creation of artworks, a fear of the absolute meaninglessness of something created by forces over which the artist has little or no control. But these anxieties are surely misplaced, since the whole point of pushing oneself to exhaustion is precisely to channel bodily failure into the discovery of new creative possibilities. (Many Artists already know this of course). When one looks at the mass of lines in McCall’s drawing, it’s difficult if not impossible to distinguish the ones made early on from the last few, however the knowledge of how the work was made, derived from its title, prompts these reflections on agency and process.

Carali McCall: Circle Drawing 1h 55 minutes (2012-24)

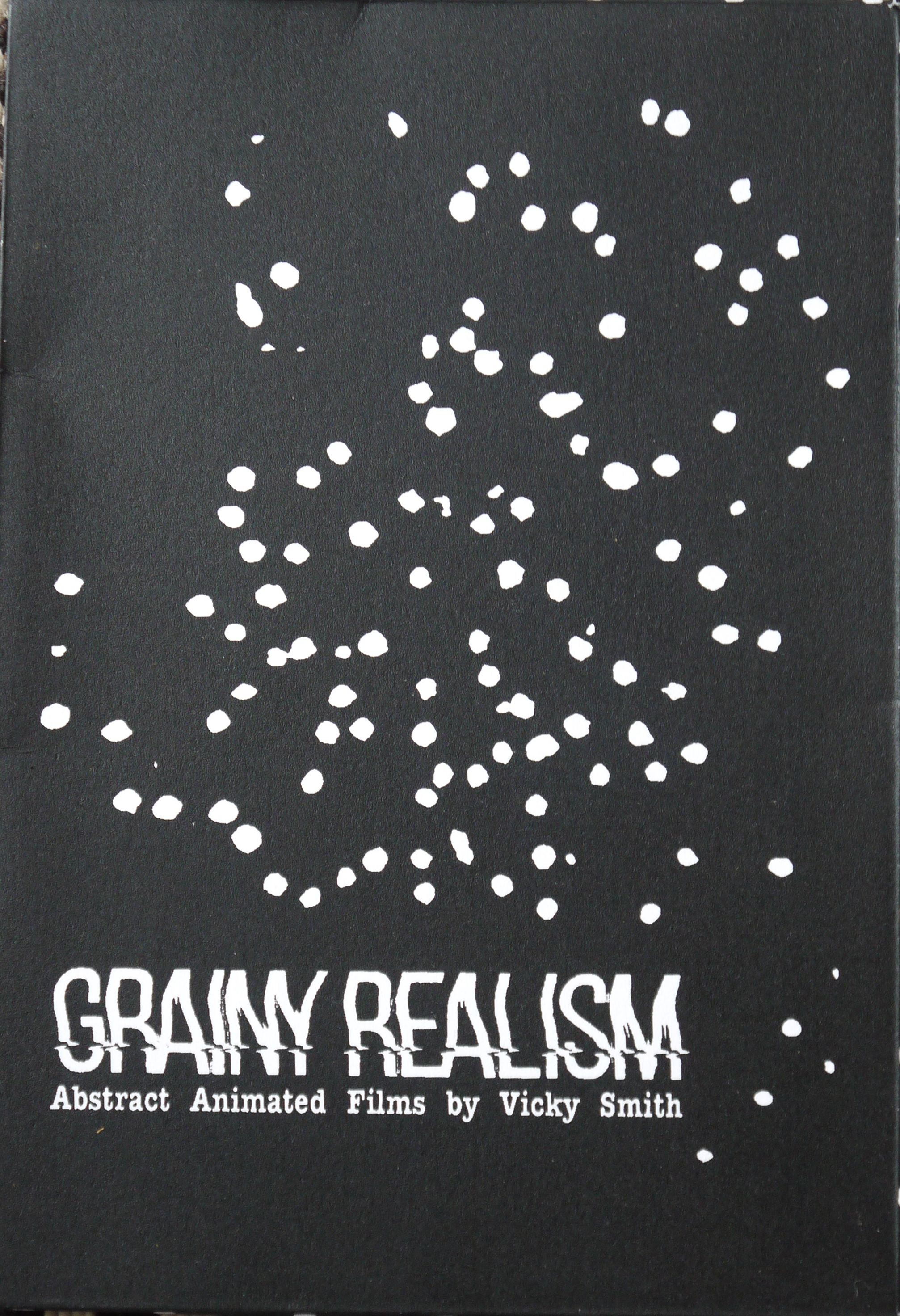

Sophie Clements’ Come to Ground (Battles) (2023) was made during a winter residency in Newfoundland. Three videos, shown on a stack of monitors, show her literally battling the elements. In crepuscular light, wearing a head torch, she wrestles with a large board or a mass of netting, or shovels snow into blustery headwinds. The work constitutes an immersion into these harsh conditions, where impossibility and futility are turned to creative advantage, art as pointless struggle, as it should be. In this regard, it’s tempting to imaginatively reverse-engineer Clements’ approach. The artist arrives in a hostile, environment. 100kmh winds are blowing, the light is fading fast and it’s minus 20 degrees Celsius outside. What to do? The elements: simple found materials, torchlight, video, snow, wind and body are constituted into a dynamic improvised struggle that evokes both Arte Povera on the material level and performance art as practiced by artists like Roland Miller and Shirley Cameron, who similarly improvised with whatever was available to hand in their durational performances of the 1970s. Their work, like Clements’, shades into a pure and disinterested form of play, or more accurately here labour, whose relationship with performance Clements throws into question. The video is very much framed as such; the performance is for/to camera, while the board and snowflakes recursively reference screen and film grain, the headtorch the projector beam. The works make visible things that cannot be seen directly, but only via their effects: light and wind. In Clements’ examples the two are fully intertwined, especially perhaps in the movement of snowflakes, where the visual thrill of pure kinesis recalls that of the first audiences of the Lumière brothers’ films, who were evidently most excited by the images of foliage blowing in the wind. Two key forms of movement, voluntary and involuntary are also entwined: the natural movement of wind and the voluntary struggle to articulate and document, to visualise the otherwise invisible.

Sophie Clements: Come to Ground (Battles) (2023)

Contact II shifted the focus from performance and filmed movement to pseudo or virtual motion and stasis. Savinder Bual and Elena Blanco’s elegant A Different Lens (2024) consists of a pair of works. One is a water-filled glass tube placed on a sheet of steel mesh suspended horizontally in a frame. The diffractions caused by the light passing through the glass tube are animated by the viewer as they walk around the work, putting them into a similarly productive relationship to its materials as McCall and Clements are in their relationship with graphite, netting, snow and wind. The viewer draws, performs even, the work for themselves, by making the mesh move, palpably connecting lines of sight with matter. The refractive properties of the tube are crucial here and have a paradoxical status. On the one hand they are what makes the work possible while at the same time rendering the experience of it highly unstable and volatile. The slightest movement of eye or bodily position in relation to the work causes apparent movement. The work is akin to a sensitive gauge that reacts to minute changes in atmospheric pressure or trembling of the earth, but here it registers human activity within the space to that human, making it a kind of individualised, personal device. The apparent movement also invites comparisons to film, since it is generated not by the work but in and by the act of perception. The second part consists of a Slinky suspended inside a glass tube. Many of Bual’s works operate in a nexus of actual, virtual, potential, implied and illusionary motion; on her website she lists Moving Things and Moving Images. Several of the moving image works explore specific cinematic effects, such as parallax, for example Myriorama (2009), which consists of hand-cranked paper loops that move at different speeds depending on their distance from the virtual (implied) camera. These video works demonstrate a strong continuity with A Different Lens, though in the latter the parallax effect is animated by the viewer. Potential and implied movements are embodied in the slinky. A form of displacement is also operating, in that the slinky, which exists only to move -its implied purpose- is trapped inside a glass cylinder, whose transparency allows the viewer to see it in order to understand what it is while at the same time understanding that it cannot move: its purpose is frustrated. Hence potential movement is displaced into a conceptual realm; A Different Lens is partly a conceptual work, whose viewer’s responses are precisely cued by its structuration.

Savinder Bual and Elena Blanco: A Different Lens (2024)

Andrew Vallance’s Never Still (2025) is the most static work in the show, yet its title addresses the question of movement, which is invariably implied in photographs to some extent. A set of different-sized lightboxes placed on the floor and facing upwards contain negative transparencies, so that the viewer is invited to imagine what the positive versions look like. A particularly vexing (and by now largely obsolete) challenge is offered, in which perceptual-cognitive limits are confronted. Anecdotally, film laboratory technicians mastered the art of ‘reading’ negatives, but for the ordinary punter this is a much harder thing to do. On this level the work is an exercise in active perception: how does one ‘imagine’ the positive image while looking at its negative? Do they cancel each other out? Because the images are representational photos of people, one is firmly on the ground of representation while at the same time being denied direct access to it. Because of the iconic character of the images, they don’t easily fall into the familiar territory of abstraction that’s always immanent in photographs, most obviously ones of surfaces where tight framing emphasises incipient formal qualities. Thereby the work operates a strong tension; there’s an urge to see what the photos really look like, accompanied by the realisation that if one could, one would be looking at a photo of anonymous people, so that on this level nothing much more would be revealed beyond the banality of yet another representation. These images are (unacknowledged) family snaps, which adds another layer of inpenetrability to their putative meaning.

By working with negative, Vallance compounds these questions, thwarting pre-given meaning on its own ground.

Andrew Vallance: Never Still (2025)

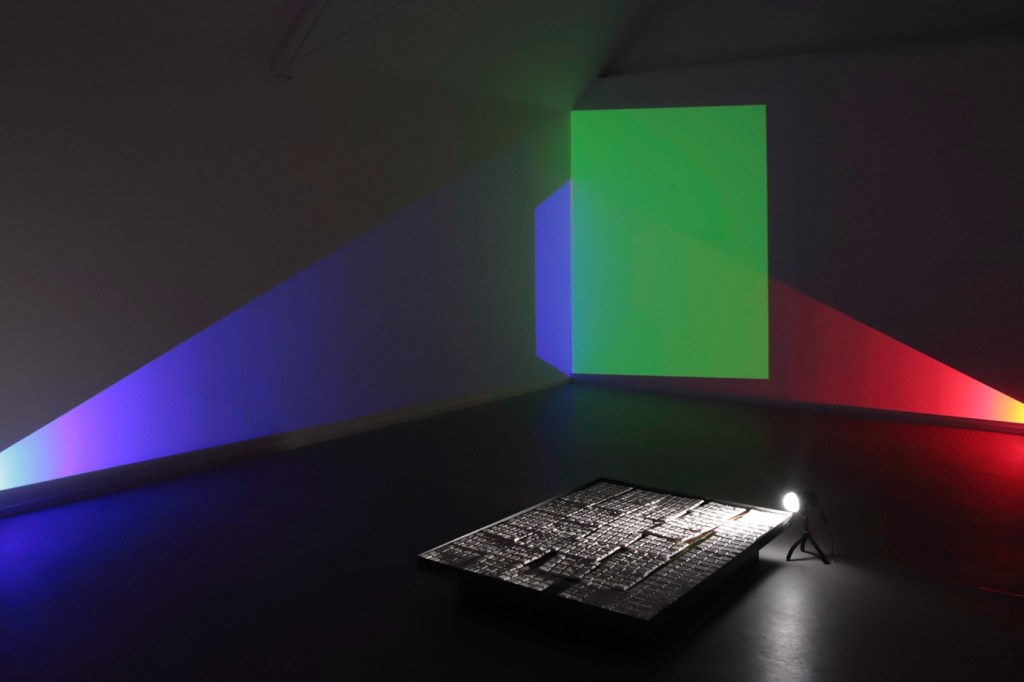

Site-conditioned works completed part II. In Simon Payne’s Floor Piece (2025) a video projector points down at the floor in the large opening between the two front rooms of the gallery. Monochrome-coloured shapes drop into frame one by one, overlapping each other to create secondary colour mixes. The work plays on flatness and depth, on the shapes as material things and as coloured light. The floor is both screen and modified surface, image bearer and illuminator. Floor Piece is designed to work in ordinary lighting conditions and as such has a rare predecessor, Michael Snow’s 34 Films (2006), which was made on 16mm film using similar techniques, but projected horizontally. By projecting vertically, Payne engages ideas around gravity and its indirect representation via the ‘falling’ shapes. Payne’s other work Corner Piece (2025), in the backroom of the gallery, is the most recent in a series of abstract colour videos that works in a similar way to Floor Piece, but which play with anamorphism through projecting at an oblique angle onto adjacent walls and thus complements Floor Piece, where the projector is perpendicular to the projection surface. Payne began working with pure colour in 2004 with Colour Bars, the bars used in video technology to calibrate the colour between different playback devices. Primary Phases (2006/12) was the first of such works to engage with the projection space explicitly. In Corner Piece, both projectors are aligned close to the wall to create anamorphic distortions, in addition to colour mixings. The images consist of two halves; firstly, a horizontal wipe, followed by a hinged rectangle. The speed of movement of the wipe is partly determined by the angle at which the projector is positioned in relation to the wall: the more acute the angle, the longer the throw, so the faster the movement, as it has further to travel. Furthermore, as the rectangular wipe-edge moves outwards it accelerates, similar to the way the speed of a rotating wheel increases in speed from the centre towards its circumference. Additionally, as the beam spreads its concentrated colour weakens and dissipates as the area of light expands. In Corner Piece, the frame is projected half on the side walls and half perpendicularly. Where the beam hits the corner line it stops expanding and the rectangular shape hinges out and back from the perpendicular wall. The hinging rectangles generate a play on three and two dimensions. Different kinds of ‘line’ are in play here, though both are the effects of boundaries: the boundary line where one wall meets the other at 90 degrees, the others formed by the boundaries between the different coloured halves of the two beams.

Simon Payne: Floor Piece (2025)

Simon Payne: Corner Piece (2025) and the first part of Jim Hobbs: Polytechneiou – When the Order breaks the Fractures Lull, (2024)

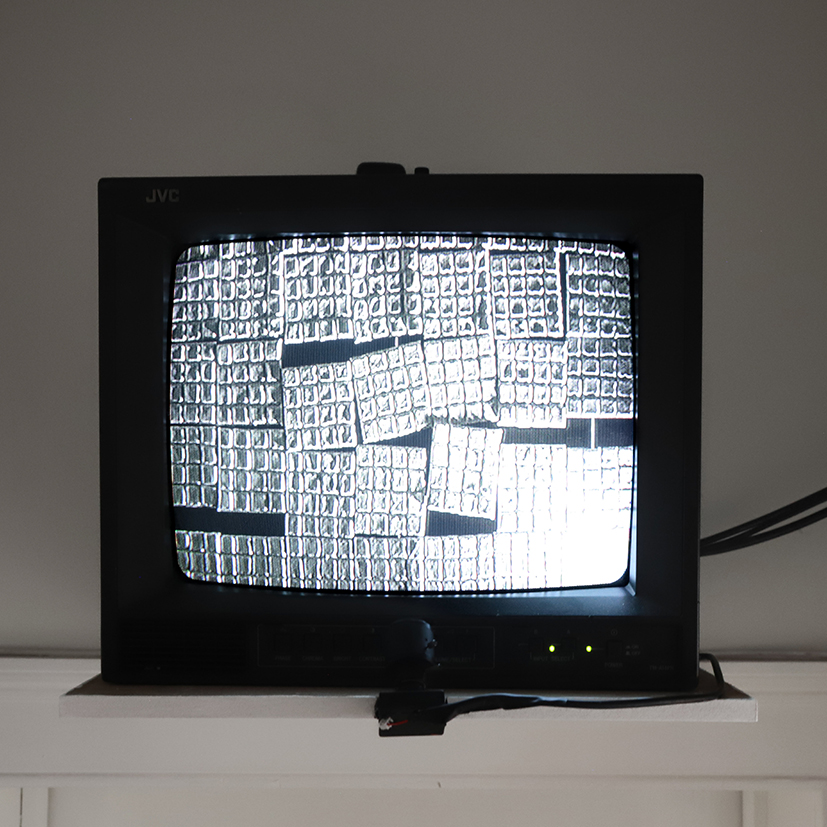

Jim Hobbs’ Polytechneiou – When the Order breaks the Fractures Lull, (2024) converts a grid of ceramic tiles into a pulsating video by relaying the analogue image via a chain of monitors, at which cameras are pointed, to a final monitor in the front room. The tiles reference the pixels from which their image is formed. The pulsation is a consequence of the noise in the signal and the circuitry, the air through which the light travels, its reflections and refractions on its way to the final monitor. By the time the image reaches the final monitor, it’s no longer clear to what extent the image is ‘of’ the original tiles: rather, it is a hybrid from which the tiles and the added disturbances cannot be disentangled. In some respects the work resembles Alvin Lucier’s iconic I am Sitting in a Room (1969) (a recording of the recording of the recording and so on) however Hobbs’ work is more disconcerting, since its point of origin, a solid object as opposed to an ephemeral sonic event, has itself turned into something more akin to an ephemeral event. Hobbs works in an unusually direct and masterful way with artificial light and its vicissitudes; we come as close to light’s direct, unmediated dazzlement as is possible. His work connects back to Bual’s visual disturbances, although here the movement is system-generated by the recursive structure. While Hobbs’ images are more or less flat, three-dimensionality is present in different ways, including the originating floor piece and equally the screens on which the images are presented, since they are very much part of the work, not simply a support. Virtual or quasi-immaterial space is present in the light rays that connect the different stages of the work (monitor to camera to monitor etc) into a continuum.

Jim Hobbs: Polytechneiou – When the Order breaks the Fractures Lull, (2024)

The combined works in these two shows constitute a multifarious, detailed interrogation and expansion of what we understand by the term ‘moving images’, of what, how and where they can be. What is the ontology, assuming there can even be one, of the technologically constituted, so-called moving image? Can movement be isolated, disentangled from its various technological inflections, disturbances, interferences, to be presented as pure kinesis? What would that look like? What changes when an image is projected non-normatively onto a floor or a ceiling, beyond its different orientation in relation to the viewer? Spatiality is also interrogated in relation to the various forms of translation between two and three dimensions; Rogers’ and Hobbs’ work that blurs the distinction between flatness and objecthood, the spatial movement required of the viewer to activate Savinder Bual’s A Different Lens, Jenny Baines’ on-off screen spatial problematic and screen assembly-as-sculpture, the vigorous temporal movements compressed into Mcall’s drawings, Vallance’s boxes that turn flat things into mysterious objects, and Clements’ recursive references to three and two dimensions in the board she wrestles with and the conical beam of her headlamp. Payne’s Floor Piece is truly two-dimensional, since no third dimension is necessary for the ‘layer’ of light to exist as it covers the floor. It is neither object, illumination nor image, but something other.